Oh, sure. My thought here was jumping to things like pay records on papyrus from the Roman period, where you have an accounting document in Latin written in Old Roman Cursive, or something like ship registers inscribed on stone in Greek.

Replies

--oh! I thought you meant something like narratology, which was some fascinating formula-like bits. Narrative, levels of narrators, knowledge, reported knowledge, etc. I did see some fascinating use of that on what Mini Pliny reported vs. could really know about Pliny's death.

That sounds interesting. Who and what are you thinking about?

Alas, I do not have names at hand! I did some narratology reading early in my dissertation research, but since I decided not to do my work on Pliny after all most of those details are buried somewhere for me. Might track it down later to avoid work & report back.

OK, I see what you mean. I was hoping historians had some kind of secretive catalogue of operations that could be used to interpret data.

Also off topic, but is there a historian who came up with a theory that "The Greeks" is a post-hoc category that "The Greeks" wouldn't have recognised themselves? I've tried searching for this a few times, but never come up with anything. Not sure where I heard it.

Huh, unsure. Also clearly wrong - by Herodotus, if not earlier, the Greeks clearly understand themselves as a defineable cultural grouping, even if they often find smaller divisions (Athenians, Thebans, etc) more important.

It probably went all the way back to after the Trojan War, where the Greeks actually got the name they use to describe themselves.

Also tricky and mostly wrong. So the word Classical Greeks use to describe themselves is Hellenes, of course, which appears only twice in Homer. But Homer uses Achaioi (Achaeans) to mean the same thing and that word appears to date from the bronze age, showing up in Hittite as Ahhiyawa.

To be clear, not as a term the Hittites gave the Greeks, but as a Hittite effort to transliterate what the Greeks - or at least some Greeks - were already calling themselves. Likewise, Homer uses Danaoi which is probably reflected in Bronze Age Egyptian 'Denyen.'

I've seen postulations that Achaean might also pop up in the Egyptian writings about the Sea People as Ekwesh.

The nature of the Linear B (=Bronze Age Greek) corpus is such that you don't get 'slam dunk' evidence either way but broadly I'd suggest it is plausible and perhaps likely that Greek-speakers recognized themselves as an ethnic group fairly early. It just wasn't the most important identity.

Among other indicators, while we're here, is that the bronze age Greek palace cultures have similar material culture - indeed, it is common to point to the emergence of more distinctive regional material culture after LBAC as a sign of the breakdown of interconnectedness.

On balance, this strikes me as most likely someone over- and perhaps misreading someone they heard attempting to stress that the Greeks tended to consider themselves Athenian/Theban/etc first and 'Greek,' like, fifth and that panhellenic thinking intensifies notably post-480 and taking it too far.

But the very oldest piece of surviving Greek literature is the Iliad and it already demonstrates a sense that the Greeks (Achaioi, Danaoi, Argeioi) are a distinct, identifiable group who can be distinguished clearly from other (Trojans, Ethiopians, Thracians, Amazons) ethnic groups.

I was actually under the impression that the Greeks got their name from Helen of Troy (as the Trojan War was the first time the Greeks were semi-unified under the Amphictyonic League), but apparently I was way off on that.

The Greeks didn’t refer to themselves as the Sea Peoples?

'Sea Peoples' is, like, 66% a modern, invented term. The Egyptian documents present a multi-ethnic coalition of peoples, some of which - but not all - are described as 'of/from the sea' and so scholars coined 'sea peoples' to refer to the entire collection of different ethnic groups listed.

It’s rather unclear where those historical “sea peoples” came from. They were described folks they attacked. But they were multi-ethnic. That is clear. So, while they could have included some Greeks, it couldn’t have been just Greeks.

Personally, I’ve always been partial to the idea that the Sea Peoples started out as pirates from Sardinia.

I think the Fall of Civilizations podcast talks about them in episode 18, on the ancient Egyptians.

I think this might be a confusion with Greece. I always ask my students how old Greece is and even knowing it’s a trick they’re usually surprised to hear the first state by that name was formed in 1830. Ancient Greek world included a lot of places (Anatolia, Italy, Egypt, etc.) that do not fit.

you might also be thinking of how they weren't literally calling themselves "Greeks" in homeric or classical times? as in, people from the times we're talking about weren't self-IDing as "Γραικοί", that's more what romans called them (and then they all became roman)

sorry, I just note that dr. devereux is responding below about whether they recognized themselves as having a shared cultural identity (100% yes) but there's also just the literal "did they call themselves that?" question

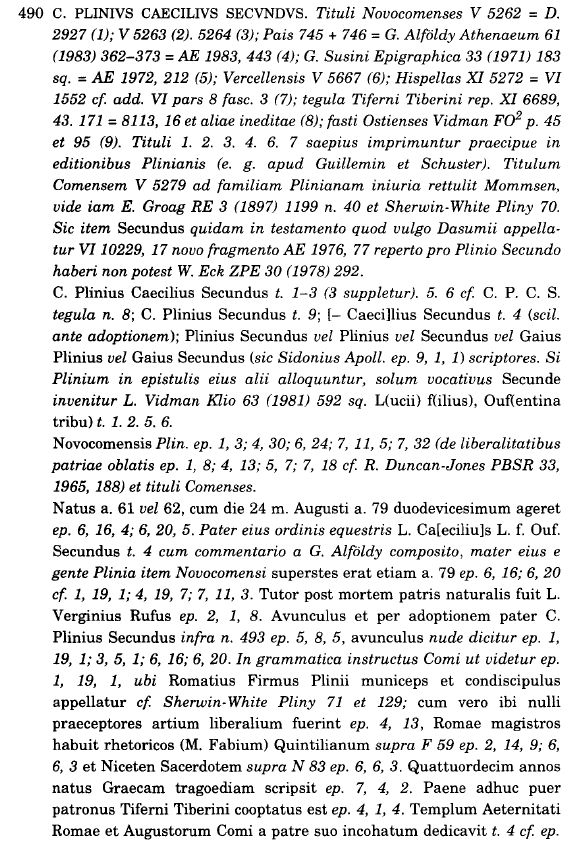

Alas, no, but we do have important reference works that might be pretty difficulty to parse (or even be aware of) for a non-specialist. Like, here's a page from the Prosopographia Imperii Romani, a standard reference work in ancient history:

I'd love to be able to read latin so that i can work with a better range of early modern texts. But even in English, the meaning and qualities of words and definitions shift drastically and you need reams of context not to get wildly off track.

One good example is "artificial", which has shifted in connotations from generally high quality to generally low quality. Is there a technical name for this shift?

Huh; I suppose that would imply a similar shift in "artifice" from emphasizing skilled construction to emphasizing the unreality of it.

Yes, exactly.

That’s psychohistory. Asimov wrote about that a fair bit.

By way of example, here is the form we actually get best preserved early Greek law code in. Archaic characters, no spaces, punctuation or line breaks, both left-to-right AND right-to-left (boustrophedon) with a ton of breaks for damage and missing stones.

Can I ask why this was made? I can't imagine the purpose but I'm sure we have some hypotheses

The photo Bret has shared above is of the law code of Gortyn, a Greek city-state on the island of Krete. Sometime in the first half of the fifth century BCE, someone inscribed the text of the code on the interior circular wall of a building. 1/

The most widely accepted hypothesis among scholars is that the building on which the law code was inscribed was most likely a Bouleuterion or meeting house for the Boule or Council of the city-state in the fifth century BCE. 2/

Cool! Thanks

Later, in the first century BCE, the Romans incorporated the wall bearing the text of the code into their Odeion or amphitheater which stands at the site, which resulted in the preservation of the code through its incorporation into the later structure. 3/

Needless to say, your average enthusiast can't do *anything* with that raw text, even if they've taken some Greek. Turning that into easily readable Greek text is the job of one kind of specialist (epigraphers) at which point other specialists get to translating and understanding it.

But no history book is going to just put the raw, unedited surviving text of the Gortyn Code into the main text of the book and expect the reader to do anything with it. Instead, you're going to get a translation into English.

Indeed it is - understandably! - quite rare to see untranslated Latin and Greek at any length in the core text of historical articles or books. Instead, we translate in the text and the original Latin/Greek usually goes in a footnote for the reader that wants to check the translation.

I’m working on translating a German text in Catholic theology from the 50s right now. ALL the quotes are in unglossed Latin, indicating the audience at the time was expected to just be able to read it. They’re making me find scholarly translations instead.

Catholic theologians? Certainly. But go back a little earlier and we'd be doing that just generally because Latin skills were almost as common as English skills today. It would, however, be normalized Latin with word breaks and no abbreviations - very unlike the original sources from antiquity.

Oh of course, I just thought it was a nice curiosity that the original audience was expected to read Latin, but the new audience is not (it’s a study of Augustine, and it deals with textual variants as well—a reminder that we don’t have originals)

The epigraphers and papyrologists and numismatists do the work everyone else relies on, and it's really quite difficult to train new ones. Preach.

I deeply admire and greatly fear all three sets. Especially numismatists. /How do they do the coin magic?/

Oh, so very much so. I took paleography and epigraphy coursework and still, honestly, I can only understand epigraphers and papyrologists as some kind of wizards. "Oh, this 13 character gap must be *these specific words*" 🙃 Even more so numismatics, where I didn't do a lot of coursework.

I once did a presentation for a Mystery Cults class on the sanctuary at Eleusis, and a particularly important article I read did so much with a tiny reference to Athens paying for bricks for the sanctuary. It was terrifying. (I guess archeologists kinda terrify me in general, in a good way.)

But numismatists are like another step beyond that. Especially once I learned how they could date specific coins by the different rates at which the top and bottom plates wore out when striking them. Dear god, it makes dendrochronology look straightforward and trivial. Numismatists! Terrifying!

Numismatics is dark wizardry.

"You see, this figure is holding a thrysus which means this coin is recalling the stylistic motif of this other coin two decades earlier, suggesting the moneyer had a connection to... Me: Wait, you can *see* what is in his hand?

And also that. I cannot make out /anything/ on coins. Like, there's a... figure? I guess? And maybe some letters? (And now I'm remembering a whole article that was clearly one stage in an extended academic slapfight over the expression of the infant about to be sacrificed in Carthaginian art.)

I'm really into an idea I got out of Mary Caruthers's Book of Memory that "the literature" includes the community who used it. I don't know if that resonates but i imagine it takes a huge amount of reading, related to reconstructing that community.